David Dixon, 'Altarpiece (D.E.D. and the C-C.C. harvesting)' (2022) [view one] plywood, whitewash, charcoal, paint, plaster, nail, hinges, UV inkjet on aluminum, 12 x 32 ft. The plywood was harvested from the Cathouse Proper group exhibition 'Diasporic Entropic Diremption and the Cross-Cultural Cross'

David Dixon, 'Reparations!' (2010), digital inkjet print on canvas with paint, ink, charcoal, fabric, thread, 24 x 66 inches

David Dixon, 'Altarpiece (D.E.D. and the C-C.C. harvesting)' (2022) [view two] plywood, whitewash, charcoal, paint, plaster, nail, hinges, UV inkjet on aluminum, 12 x 32 ft. The plywood was harvested from the Cathouse Proper group exhibition 'Diasporic Entropic Diremption and the Cross-Cultural Cross'

David Dixon, 'The Sins of the Father' (2022) rusted nails (from shipping pallets), bronze, copper, cloth, paper, ink on book by Thomas F. Dixon, Jr., published 1912, 7 x 5 x 1.5 inches Contains the text "The Grave Digger", by David Dixon, link to below

David Dixon, 'The Traitor' (2022) stainless steal, rusted nails (from shipping pallets), bronze, cloth, paper, ink on book by Thomas F. Dixon, Jr., published 1907, 7 x 5 x 1.5 inches

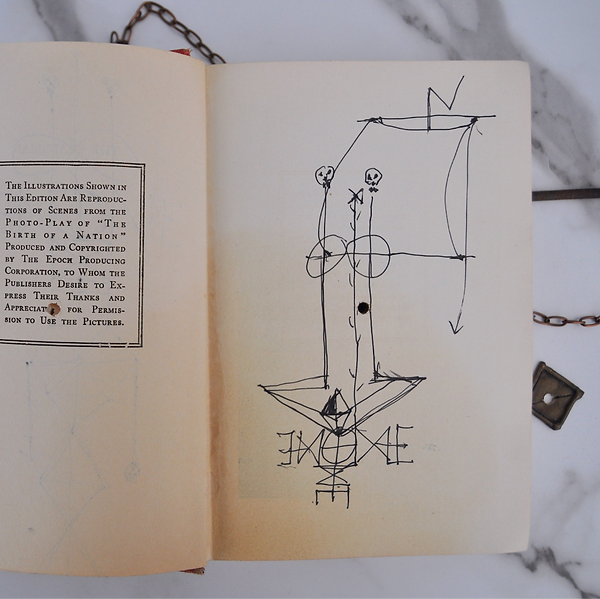

David Dixon, 'The Clansman III' (2022) rusted nails (from shipping pallet), bronze, silver solder, fabric, ink on book by Thomas F. Dixon, Jr., published 1905, 7 x 5 x 1.5 inches. This book has interior drawings.

David Dixon, 'The Root of Evil' (2022) stainless steal, rusted nail, bronze, fabric, paper, ink, graphite on book by Thomas F. Dixon, Jr., published 1917, 7 x 5 x 1.5 inches, featuring the name and signature of the artist, David Dixon, replacing that of the author.

David Dixon, 'The Clansman II' (2022) copper, rusted nail, bronze, fabric, paper, ink on book by Thomas F. Dixon, Jr., published 1905, 7 x 5 x 1.5 inches. This book has interior drawings.

one of many interior drawings in 'The Clansman'

one of many interior drawings in 'The Clansman'

Press Release

Cathouse FUNeral / Proper, a gallery project based in Brooklyn and directed by artist David Dixon, is partnering with Beacon’s own Mother Gallery, directed by artist Paola Oxoa, to produce an installation conceived and executed by Dixon for the historic Mechanic’s Savings Bank on Main Street that, until recently, had been occupied by the Star of Bethlehem Church. The installation takes into consideration these generations of building use by installing, in the building’s vast main space, a free-standing wall evoking an altarpiece, which embraces, through its form and proximity, the bank’s original, in situ vault. The wall/altar is constructed like a stage set and built from what Dixon calls “harvestings,” physical remnants (in this case, sheetrock and plywood) preserved from the design conditions of his gallery’s past exhibitions, then repurposed for off-site construction and installation.

This is not the first time that the Cathouse gallery project has visited Beacon. In the summer of 2017, Dixon and Oxoa joined forces to produce an exhibition titled 'Leaving Home: Cathouse FUNeral Migrates North' that was installed in the raw space that is now Brett’s Hardware on West Main, and was reviewed in Beacon’s local paper,“The Highlands Current.” 'Leaving Home' was conceived, in part, as a reflection on “crossing-borders,” ergo immigration; the show asserted an eclectic sensibility, concerning itself with overcoming borders physical, psychological, and celestial.

Our current exhibition, 'Bank. Church. Cathouse.', too, addresses relevant cultural and, even, mystical concerns. The subtitle “The Sins of the Father” references an eponymous book written in 1912 by the infamous Thomas F. Dixon, Jr., author of 'The Clansman' (1905) and its adaptation to script for the film 'The Birth of a Nation' (1915). Although there is no direct family relation between this author Dixon and our artist Dixon, over the years, the artist has been investigating shared cultural overlaps. The artist Dixon has meaningfully manipulated and installed a first edition copy of the author Dixon’s 'The Sins of the Father'; it sits near the wall/altar functioning as a kind of liturgical “holy book of evil.”

Inserted into this book is a two-page text (available as photocopy) titled “The Grave Digger,” written by Dixon, the artist. In this text the somewhat esoteric term sensus communis is referenced. This term most directly translates from the Latin as “common sense,” and has a long history in Western, perhaps more generally, human thought, dating back to, at least, Aristotle. The sensus communis in classical thought was associated with the “world soul,” which all of humanity was thought to share in by way of their individual sixth sense, the “common” sense. Sensus communis connected one to others and to the transcendent, but also unified the five physical senses (perception) in the individual’s mind and/or soul.

Within the bank’s original, walk-in vault an upright painting is installed that depicts a clash of cultures. On the canvas surface is a photographic image, appropriated from a museum catalog, of an African Fang reliquary figure standing atop a bark basket that would have contained generations of Fang ancestral skulls. European missionary and colonial efforts physically and spiritually severed this relationship of sculptural figure to skull, taking the sculpture while disposing of the ancestral skulls. Here, the basket is illusionistically filled with a cluster of skulls derived from Leonardo da Vinci’s analytic drawing attempting, but failing, to locate the sensus communis in the human brain.